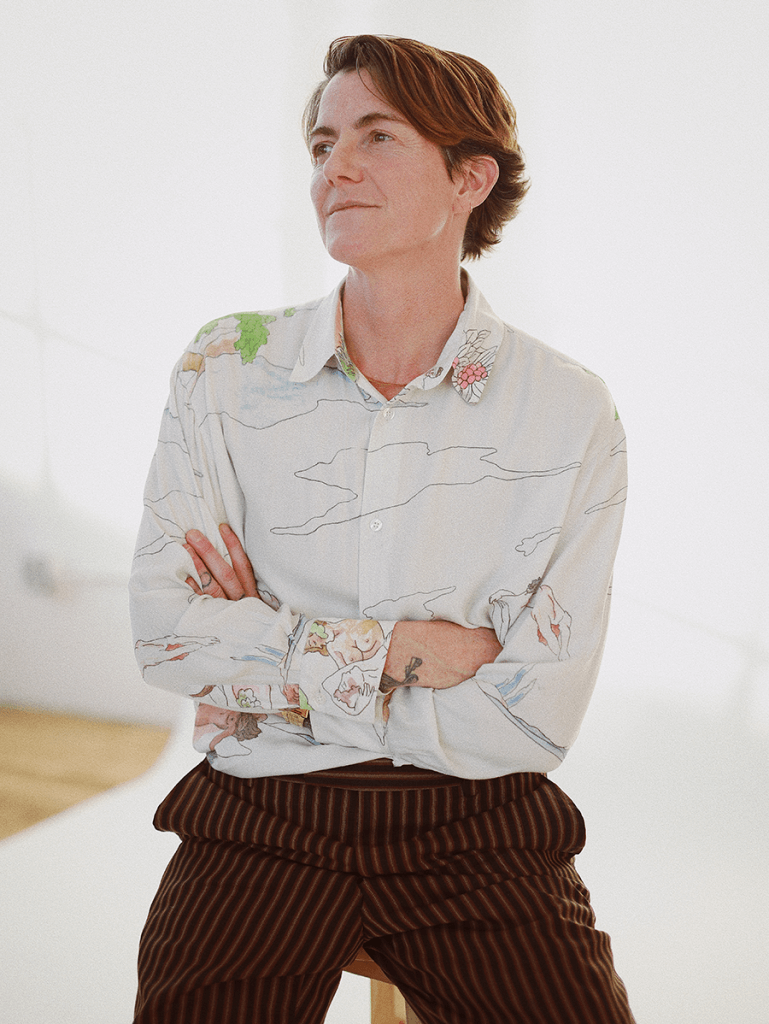

You know Cas Holman as the brilliant mind behind Rigamajig. Now she's turned her play expertise toward a new challenge: helping adults rediscover how to be playful. Her new book, Playful draws on psychology, history, art, and design thinking to make a powerful case for the vital importance of play for grown-ups in a world obsessed with productivity. What made someone who's spent decades perfecting play for kids turn her attention to adults? We sat down with Cas and asked about her journey and what she learned.

Jane: Today we're talking with our very own Cas Holman, the brilliant mind behind Rigamajig and other innovative play products loved by children, parents, and educators around the world.

Cas has recently turned her attention to a different audience entirely: adults who've stopped playing. Her new book Playful explores why grownups desperately need to rediscover play—not only for fun, but for their mental health, creativity, and problem-solving abilities.

Cas, what sparked your journey from designing toys for children to writing about play for adults?

Cas: Well, in the time that I've been working with and designing for play for children, I always consider the adults and the educators and the museum staff. I think about the whole system in which the child's play is supported.

When I'm designing a play space or a learning material, I'm always thinking about the adults in the room. But what I found was that as I talked about it and talked to people, they would kind of pull me aside afterward, or the question would come up after a lecture or a presentation, and they'd say, "So what about adults?"

I'd respond, "Here's where you can store the things, or here are the prompts that you can give to children." And they said, "No, no, but what about us for play?" At first I was kind of alarmed, but it started coming up every time. So over the last 20 years, I've had to answer the question, and I started thinking more directly about what is it about adults and play.

Why is it hard for us to access our own intuitively driven free play in particular? I think we're often really great at sports and video games, and we might go dancing or have some intramural things. But I really started to realize how hard it is for adults to play. And so that's what led to the book.

I also realized that I had quite a bit of experience helping adults play through my teaching as a professor of design and art. A lot of what I was doing was helping my students reconnect with their play, because art making and design is largely play for a lot of people.

I also realized very early on that my skill set is in designing and thinking and facilitating play for others, but I wasn't necessarily so skilled in writing a book. So I had to figure out how to make that process play for me, because my work is also my play. When I'm designing things, it feels like play, and I connect with my own play and enter a flow state.

For the first year or so that I was starting to work on the book, it didn't feel like that. So I realized I needed to find a collaborator, find somebody to make it play with, and someone who had a skill set that I did not. We connected with Lydia Dinworth, who is my co-writer and was a wonderful collaborator for me, so that the process became play. We had a lot of playful conversations, and the way that we organized and sorted the book was really playful.

Jane: The playful products you design are intentionally open-ended—for example, Rigamajig. How does the same principle apply to adult play? What would an open-ended approach to work or problem solving look like?

Cas: With work and adults, it depends a lot on the work that people are doing. But I think largely, one thing that prevents adults from really diving in and feeling good in a playful approach is our attachment to success.

I think we tend to be very attached to doing something right or doing it well. We're also hesitant to look stupid, for lack of a better term. That's one thing that I heard from people quite a bit. They're like, "I don't want to look stupid, or I don't want to feel stupid by not knowing the answer." It makes us feel good when we do something we know how to do or when we do something that we know we're good at. There's that reward of success, and we're like, "I am a smart, competent adult"—that's what I'm supposed to be.

I think there are lots of ways that we can let go of that need to do something right or do something well. In play, that's much easier. It's much easier to experiment and explore and not be so caught up in the outcome or the right answer.

In a lot of people's work, that looks like different things. In some cases, it's knowing that your boss is also going to support you in trying some new things that might not have a predictable outcome or the outcome they're looking for, but maybe will lead you somewhere else entirely. The creative process, in order to really lead you somewhere new, has to allow for things that you don't really even know what you're going to do with.

It's also letting go of our need to be efficient or productive—the fastest way there, the most direct way. That's probably the one that you've done before, or you know the outcome of, and it's not very playful usually.

Taking a playful approach to solving a problem would mean that you let yourself meander on the way, or let yourself explore something that you're not sure about. That typically also means having the support of everybody around you, so that your team, or your boss, or even the people who work for you directly—everybody is on the same page, and you don't fear judgment for doing something in an odd way, or doing something that has a strange outcome that you couldn't have known.

Jane: The book mentions that play can help with everything from well-being to innovation. For educators listening or reading this interview, how might embracing personal play improve their teaching?

Cas: Educators are interesting, because I think we spend so much time, especially primary education teachers K through 12, supporting our students' play. There's a parallel play that happens fairly often where they may be playing alongside the students, or if the students are in a flow of play, then the teacher can step back and observe.

It's a new habit or a new skill to actually play ourselves. One of the things that I suggest to people is that when they are on their own, removed from the classroom where they have habits that are ingrained and probably pretty necessary in order to support the environment for the children and students to feel safe playing—that on your own time, you might let yourself do the thing that feels unproductive.

I think productivity is tricky. I hear from teachers who say that when they're at home, even on the weekend or in the evenings, they feel like their time is so limited they have to make the best of it. The first step is realizing that play is an excellent use of your time. The same way you prioritize play the way that you prioritize exercise or sleep or eating well, then you might let yourself dilly dally, or even tinker around.

In some cases, even rearranging the living room or cleaning out a junk drawer might feel a little bit playful, and that could be a step toward letting yourself do the thing that's like—those are both productive, but they also might be something that you're getting something out of. Going through things, reorganizing and sorting—sorting is play for children as well.

As adults, that can actually be playful. Especially the organizing—we don't have very much... there are a lot of things in our lives that are uncertain and don't feel like they're under our control. So I think that for me, in the last few years in particular, sorting and organizing has become part of my play in a way that it wasn't before. I'm calling it play instead of cleaning up, because I'm intuitively driven to do it, and I have a similar flow state, and I feel satisfied, and I can tell that it's fulfilling something in me that I really need—which is to have control over something, even if it's my silverware drawer.

Broaden your idea of play, and let yourself do the thing that you might otherwise think is not essential. That might help you step toward doing something that's actually more playful in the way that we think of it—creating something or making something that might be considered art, playing with your dog, or dancing around the living room.

Jane: So for educators, does it mean that they need to be more playful at home or in the classroom? And how will it affect their teaching?

Cas: I think it will make the classroom more enjoyable for them. If you feel better while you're doing your job, you're better at your job and definitely connect with the students more because you'll be speaking their language. If you're fluent in play, and the child's primary drive and primary language is play, you'll be able to see what's going on in their play—the nuance of the developmental milestones and things that they're learning and things they're expressing as they're playing are going to be much more visible to teachers if the teacher is fluent in that language, which is play.

If the teacher can connect to their own sense of play, which I also think can happen when they observe play... observing the students and looking for moments that they're connecting with each other, or even having new discoveries in their drawings, or with Rigamajig, for example, as they're building with Rigamajig. There are all kinds of things that are happening, even in things that might look like conflict, that can happen in play in a way that the child is motivated to resolve it.

That's really powerful when the child can have a moment with a peer that might look like conflict, and if they can resolve it on their own, that brings them whole new skills that they wouldn't have if someone else were resolving it for them. By getting more skilled at playing themselves, the teacher is probably going to be better at observing and letting children, or helping children, work through things amongst themselves and on their own.

Jane: One final question.. If someone could only take away one core message from Playful, what would you want it to be?

Cas: Play has value. In the book, I suggest that we have a play voice and an adult voice. In our adult lives we tend to prioritize productivity or efficiency or work, and I think we get in habits of shutting down our play voice. I have some pointers for how to listen to your play voice and hear it. As soon as you start listening to it, your play voice gets empowered, and it starts suggesting more ways you might play. I think we all can listen to our play voice more and realize that it's there to help us and not trying to make us look silly or humiliated in public. Not just our children and students, but ourselves and our communities will be stronger if we let ourselves play together. Because play is critical to being human.

Jane: Thank you, Cas. I can't wait to read the book! When is it released?

Cas: It'll be out October 21st, and actually, pre-sales are starting now, so you can pre-order it!

25% off THREE DAYS ONLY: 07/09 - 07/11

Pre-order Playful at Barnes & Noble with code PREORDER25